![]()

SIX MONTHS IN SINGAPORE AND WHY HUMOUR CAN HELP

I was a bit reluctant to accept the invitation to spend six months in Singapore, because all that I knew about the country is that you can get sent to prison for spitting chewing gum on the pavements.

But I am so glad I went. It altered my perspective on the world. However difficult times are now in the West, I’ve seen that there is another way of looking at things.

And I’ve found that I do rather like clean pavements!

When I came here in January 2017, I was quite depressed about the way that things were going in the West. First with Brexit, then with Donald Trump.

It seemed as though we were locked into patterns of hatred that go back for millenia. The Scots and Welsh and Irish hate the English, the English hate all foreigners, the Greeks and the Turks hate each other. The Russians and Ukrainians pretend to hate each other, because having an enemy is a useful resource for politicians. The Palestinians and Israelis really do hate each other. And everybody hates the Germans. Except those who hate Americans more.

But coming here gave me a new outlook on hatred.

Now, I see that all those hatreds seem remote and trivial. Real hatred is what the Malaysians, the Vietnamese and the Indians, and many Chinese, feel towards China. And everybody including the Chinese hate the Japanese. But they love Japanese food.

When bad things happen, my instinct is to respond by writing, and then I turn to humour, because laughing is a way to cheer yourself up. Humour doesn’t change the world, but it can help us to survive it. Humour cheers us, it empowers us, and it shows that we are really just so much more clever than the idiots running the world at present. They can take everything away from us, but they can’t stop us laughing at them in our hearts.

So what is humour? I thought I must attempt a definition, and being in the East, I turned to Confucius, who did wisely observed the link between comedy and tragedy. He said that “The funniest people are the saddest ones”. But I have come to the conclusion that Confucius was more cut out to be a thriller writer, when he said,

“Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.”

Many philosophers in the West from Aristotle onwards, have tried to define humour, but they all make it sound very dreary and I won’t summarize them here. I was particularly drawn to Umberto Eco’s theory, that comedy arises out of transgression – that is, out of breaking rules. Aha, I thought, there will be lots of humour in Singapore there, because there are lots of rules to be broken.

According to Eco, humour arises when people break rules of propriety, like misbehaving at the table, or rules of hierarchy, when they misjudge someone’s social status, rules of language, when they mispronounce words or use the wrong word, like Mr Micawber in David Copperfield, who said “I am battered by the elephants” when what he meant to say was “I am battered by the elements.”

The trouble is, to understand that kind of humour, you have to know the rules that are broken – you have to know the language or the culture they pertain to. And maybe thats why humour doesnt travel very well between countries and cultures.

At first I was baffled by the sign on the MRT that said No Durians. I had no idea what a durian was. I imagined from the tone of the warnings that it must be some kind of spiky weapon used by terrorists. So I rushed home to Google it.

Fruit! There’s a rule against fruit?

Imagine my glee as I copied and pasted that photo to my friends in UK, thus confirming all their prejudices.

![]()

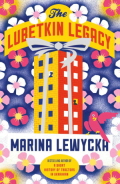

OXFAM AND AMNESTY SHORT STORIES

I write very few short stories - I find them much more challenging than novels. But this year, I published two.

I contributed a story called The Importance of Having Warm Feet to the Earth-Air-Fire-Water fundraising anthology for Oxfam, one of my favourite charities (and also a major player in my wardrobe). I had such fun reading from it at an Oxfam promotional event last year, and going shopping afterwards.

http://www.oxfam.org.uk/applications/blogs/books/?p=2007

I was also a proud contributor to the Amnesty International short story collection called Freedom in celebration of 60 years of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. You can read about the collection here:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/aug/27/authors-donate-stories-human-rights

![]()

Why I Write

(Published in the Guardian 12th March 2008)

1. What was your favourite book as a child and why?

The first book I owned was Mary was Five & The Black Rock by Honor Appleton. I was given it as a school prize when I was about five. I adored The Black Rock, with all those scary cormorants, but I thought five-year-old Mary was a bit of a drip. Later, I was given a book of poetry, and that was the start of a long infatuation. I was especially drawn to sentimental rhyming writers like Alfred Lord Tennyson and Walter de la Mare. I can still recite a big chunk of The Lady of Shallot after a couple of glasses of wine. And don't get me started o n Nicholas Nye.

2. When you were growing up, were there books in your home?

There were, but not very many, and mainly library books; my parents' English wasn't so good when they first came here, and books in Ukrainian and Russian weren't readily available in Doncaster and Gainsborough. But they were great users of the public libraries, and I worked my way through the children's sections.

3. Was there someone who got you interested in reading books or writing?

I had some wonderful inspirational English teachers from Wheatley Hills primary school in Doncaster right through to Grammar Schools in Gainsborough and Witney; if you're reading this, thank you Mrs Holmes, thank you Mr Van Wyck.

4. What made you want to write when you were starting out?

I started writing when I was very young - I wrote my first poem when I was four (it was about rabbits). I think it was the sounds and rhythms that captivated me - it was like creating my own magic spells.

5. Do you find it easy? Has it become easier over time?

No, it gets harder. I'm more self-conscious now. It was easy when I thought no one was going to read it.

6. What drives you to write now?

What drives me most now is a sense of urgency - of time running out. So many things I want to say, stories to tell, techniques and ideas to experiment with, even to make mistakes and learn from them, and so few not-completely-gaga years left in which to do it all.

7. When it comes to writing, do you have a daily routine?

If I can start early - about six am - and go through to lunchtime, I'm most productive. Once I start answering my emails or listening to the news, I'm finished.

8. Do you find working alone difficult?

Actually I like being on my own when I'm writing, and I think I'm probably not very pleasant to be with - I get very absorbed in the world of the book I'm writing. The loneliest thing is the touring and promotion - the feeling of being on display means you can never quite relax.

9. What was the best advice you received when you were starting out?

Of all the dozens of rejection slips I received for my unpublished book, only one gave me any advice. "Show, don't tell." (For example instead of saying someone is a bully, you show them behaving in a bullying way.) That's such a simple and useful hint. Thank you, Robyn Sisman.

10. What advice would you give to new writers?

Go on a course. I'm sure without the creative writing course I did I would still be unpublished. I did learn some very useful things, but most importantly, my course brought me to the notice of my agent.

11. Is there a secret to writing?

I suspect there is, but I don't know it. I just spend hours and hours and hours writing and re-writing, and then deleting it all and starting again. I sometimes think there must be an easier way - if anyone knows the secret, please tell me.

12. What are you working on now?

I'm working on my third novel. It's about an old lady who lives in a house with seven cats. And it's about the conflict in the Middle East. And it's about the end of the world. Among other things.

This Writing Life page one | This Writing Life page two >>

![]()