![]()

Marina Lewycka's father doesn't quite recognise her now

![]()

NIGEL'S STORY

- 'I SAW HIM CLINGING TO A LAMP POST'

Published in the Guardian August 2007

Before the floods in central England hit the news, we had some floods up in Yorkshire, you know. I was away from home when they happened, stuck on a train that couldn't get beyond Derby. I had to spend the night with a friend in Birmingham, and glued to the television, we watched the floodwaters rising in my home town. In one shot, as the rescue helicopter circled over the stricken area, you could see the figure of a man clinging to a lamp post with the water swirling around him. Today, Sheffield being the village it is, I met that man.

Nigel Robinson is thirty five years old, and does the books and payroll for a large taxi-firm. On June 25th he'd set out from the office to collect some paperwork from an office supplier. It had already started to rain. The traffic was crawling. "It's nothing but a bit of rain," he thought. At one point, when he seemed to be stuck, he decided to turn the car around and head back into town, where he thought he'd at least be able to get a bus home. He was still thinking it was just a bit of rain. The traffic was jammed, and the water was a few inches deep. His car - a trusty J-reg Astra - stalled, and he couldn't get it going again. By now, the water was lapping at the car door. It was obvious this was more than just a bit of rain. He had no choice but to get out and walk.

Suddenly, the water was up to his chest, rushing like a river. He tried to get across the road, but was swept off his feet and carried along in the flood, struggling to keep his head above the filthy sewage-tainted water. "I really thought this was he end," he said. But the water threw him up against a lamp post, and he clung on for dear life. This was the clip I saw on the news bulletin, endlessly repeated. "Oh, how embarrassing," he said when I told him. But what I wanted to know was - what happened next?

It wasn't the rescue helicopter, it was the workers in the Chamber of Commerce across the road who spotted him, and reached out with a long pole - maybe a flag pole - and hauled him to safety. Ok. Phew. That was it, then? Safe at last? No, Nigel's adventure had only just started.

As the water rose, the Chamber of Commerce building itself got flooded; they managed to attract the attention of the rescue helicopter and were winched up from the roof, Nigel included, and whisked to safety in the Meadowhall Shopping Centre, a few miles away, where an emergency centre had been set up. They were given blankets and hot drinks.

But the waters carried on rising. They were evacuated to the top floor of the shopping centre. By now, Nigel was shivering and throwing up uncontrollably - the filthy water he'd swallowed obviously hadn't done him any good. And Meadowhall itself, where dozens of people were sheltering, was at risk. So the helicopter was called in again, and Michael was winched up for his third rescue of the day, and flown to Rotherham General Hospital.

Meanwhile, just a few miles up the road, cracks had appeared in the giant Ulley Resevoir. If that was to be breached ...

But it wasn't. Nigel went home the next afternoon to the maisonette in a nineteen fifties council estate in a suburb on the south side of Sheffield, where he lives with his partner, a nurse, and his teenage step-daughter, and tried to make sense of what he'd been through. The following day, he reported in to work as though nothing had happened.

'So what did they make of your story, at work?'

'The boss said, you'd better watch out - all the women will be after you.'

'And were they?'

He blushes bashfully.

'And so - how do you feel now?'

'Well,' he hesitates. His ordeal still weighs on him, but he doesn't want to be thought an attention-seeker. 'I wouldn't want to

go through it again, like.'

![]()

A Short History of Tracking Down my Family in Ukraine, published in the Observer 2005

Observer Article

![]()

My parents hadn't talked to me about the difficulties of their lives; they had wanted to shield me, I suppose, from the awful things they had been through. But a couple of years before my mother died, I did talk to her, and recorded what she said on tape. That tape, I thought, would one day be the basis of a novel.

One of the wonderful things about writing, though, is that the idea you start out with is not necessarily the one that gets written. The characters have a way of taking over, and that's what happened in my first novel, A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainaian. I had thought I would write something profound and sad about the 'human condition', and I ended up winning an award for comic fiction. Maybe the human condition is funnier than we think at the time.

But my mother's story is in there, threaded in among all the other stories, and doing the background research for it on the internet, I found much more than I had ever thought would be possible. Late one night I came across a Russian family-search website. I typed in my surname and my mother's maiden name, sent it off, and forgot about it.

It wasn't until a whole year later, when the book was well on its way to publication, that I found three mysterious letters in Cyrillic script in my email inbox. One of them was from someone in Israel who claimed to be related to an uncle of my grandmother. Hmm. A likely tale, I thought. I had forgotten all about the family search website. The other two seemed even more unlikely: one claimed to be from my father's niece, the other from my mother's sister. I thought this must be one of those internet scams where I would be asked to send huge sums of money to these putative relatives. But, just in case, I replied, with a couple of 'trick' questions, that only real relatives would know the answer to.

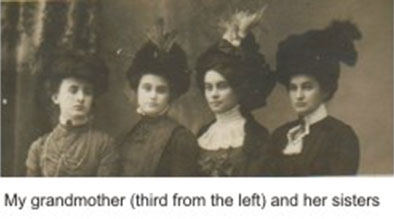

The letters that came back brought tears to my eyes. Not only did they answer the questions, but they sent a whole family tree. And there were photographs - they must have scanned them in - of my grandparents whom I had never met, of aunts, uncles, cousins - there are dozens of them over there! Photos of my parents as children and later as young adults.

How familiar and yet how different they looked, in their quaint 1930s-style clothes, their faces unlined, and laughing as though they had no idea what life would throw at them.

How familiar and yet how different they looked, in their quaint 1930s-style clothes, their faces unlined, and laughing as though they had no idea what life would throw at them.

And alongside all the old sepia photographs, some colour snaps of my new Ukrainian family: my cousin Marina, who is the daughter of my father's sister, now in her sixties and living in Moscow with her daughter and grandchildren. And my cousin Yuriy with his mother Oksana, who is aged 86 and still living in Luhansk. Oksana is my mother's sister; they hadn't seen each other since 1943. This summer, my daughter and I went over to visit them.

People ask: well, what were they like? Were you surprised? Actually, what surprised me was that, in spite of the war and the huge upheavals that split Europe and our family in two, we are all so alike.

My cousin Yuriy is six years younger than me, and, like-me, is a part-time lecturer in an academic institution. His mother Oksana, my new-found aunt, is seven years younger than my mother would have been, and is uncannily like my mother was when she died; it was wonderful but heartbreaking, as though my mother had suddenly come back to life, and was holding me in her arms and laughing and kissing me in a way that was the same, but subtly different . My daughter Sonia, now twenty-eight, is so like my mother was at that age that all the relatives fell on her with big hugs and cries of "Our blood! Our blood!" I think they were a bit disappointed in me - I look more like my father.

But although we have remained very alike as people, the great difference between me and my new Ukrainian family, which made me very sad to see, is how poor they are, and how hard their lives had been. Seeing the cramped conditions in Yuriy's tiny one-bedroomed flat, which he shares with his partner Lyuda, a lawyer, made me realise how easily I take my roomy house and my holidays abroad for granted.

Aunt Oksana's gracious but crumbling flat dates back to1912, and has been in the family for some seventy years - my grandmother Marina, after whom I was named, died here of pneumonia in 1952. From the outside, the block looks almost derelict; inside, the flat is decidedly Spartan - it needs a lick of paint, a new bathroom, and a central heating system. It is stuffed full of photographs, framed on the walls, in albums, in envelopes in drawers, everywhere you look. Of all the modest wealth our family once had, this is all that is left. And yet what took me by surprise was not how different it was, but how at home I felt.

Soon I learned the secret of how Lyuda and Yuriy survive in their tiny flat: they have a dacha. Every weekend, they pile into their ancient BMW and drive some thirty kilometres to a settlement on the banks of the river Donets. Sometimes Oksana comes too. In fact their 'country cottage' is bigger than their flat in town, with two bedrooms, a comfy sitting room, a kitchen, and a vine-covered veranda where we took our meals. What the dacha doesn't have is a bathroom. The only water is piped in a rusty iron pipe from the river, and is definitely not for drinking. The toilet is an earth closet.

However, Yuriy has ambitious plans to create a new bathroom at the bottom of the garden, which will even have a warm sun-powered shower: a black-painted barrel of water on the roof. The garden at the dacha is a typical Ukrainian garden, every inch planted with fruit trees, strawberries, lettuces, tomatoes, carrots, potatoes, onions, beans. No lawn. No deck chairs or sun loungers, or other such softie nonsense that I have come to take for granted. No, the dacha is where you come to grow your vegetables, gather and bottle your fruit, brew or distil whatever tempts your palate, and relax with a few glasses of vodka and a fabulous meal in the evening.

Their dacha is one of maybe two hundred in a sprawling community of similar dachas connected by dirt roads, with everyone working away on their plots in the brilliant sun, chatting and swapping seeds, fruits and cuttings. The atmosphere is like a giant allotment. You have to be very careful what you say as you walk by on your way down for a refreshing dip in the river. A friendly word, and you will be whisked into one of the cottages, forced to sample jams, pickles, preserves, smoked fish, and last year's vodka or blackberry wine, while the proud owners stand over you and keep refilling your plate and glass, and you won't be allowed to escape without a basket of apricots and a couple of giant marrows to stagger back with.

Maybe it's a nostalgic recreation of village life for city-dwellers who still have a foot and a heart back in Ukraine's rural past. It made me realise why my mother's English friends were all gardeners, and why she loved nothing more on a summer's afternoon than to walk along and chat to everyone working in their front gardens.

The idyllic village communities still exist in Ukraine, but there is also a huge amount of suffering and poverty in the countryside, especially among the old people. During our last week, Yuriy took us out to visit some more relatives at Krasniy Dirkul, a tiny village about as far east in Ukraine as you can go, right on the Russian border. Here we met my cousin Lena, whose grandfather and my grandmother were cousins. She and her husband Valeriy have a cottage and a smallholding in a tiny settlement on the banks of a lovely willow-fringed river. They keep a few chickens, grow their own vegetables, pump their own bore-hole water, and look after their grandchildren all through the summer months when the parents' jobs mean they cannot escape the city.

It is blissful in the summer; in the long bitter winter, it is a real struggle to keep warm and to get enough food to live. There are no shops within walking distance so you have to survive on what you have managed to pickle and bottle. The state pension is negligible, coal is unaffordably expensive now they have closed most of the mines, and fresh food is impossible to come by. As always, it is the old people suffer the most.

My eighty-year old aunt Alevtina, who is the widow of my mother's younger brother, is an example of just how tough you have to be to survive. She lives in a tumble-down cottage a couple of fields away, where she keeps ducks and geese, and milks her own cow. She is also a school teacher, and she still walks the four kilometres there and back every day to teach at the local school. Her subject? English - and although she has never been to England, and in fact we are the first English people she has ever met, her pronunciation and grammar are superb.

Lena is a talented cook, and she is disappointed that we are only staying for four days; it means she will have to stuff a fortnight's worth of food into us in less than half the time, and she certainly does her best. At one point, when we decline a fourth helping of cherry-filled dumplings served with lashings of sour cream, she throws her hands up in the air, and cries, "Oh Lord, what sin have I committed that you have sent me such a useless bunch of guests who won't eat anything!"

She does teach us the recipe, though. Delicious, but complicated and time-consuming to make. And the cherries just aren't the same over here in England.

And now the mystery of how we found our Ukrainian family, and how they found us, is revealed. Lena's sister, Olga, comes down for a visit. Olga is working as a computer programmer in Israel, and it is she who, in a quiet moment, typed my mother's family name into Google. And up came my entry from the family search website.

Discovering my Ukrainian family has changed my sense of who I am. I am still English, an English writer. And of all the privileges growing up in England gave me, having access to the wonderful English language is the one I value most. But I am an English person who loves gardening, who can swap family banter in Ukrainian, I can do a mean beetroot soup, and I am still working on that cherry dumpling recipe.

![]()

This life: Marina Lewycka's father doesn't quite recognise her now

11th June 2008

Dad is sitting in his wheelchair in the corridor when I arrive at the nursing home. My first glance takes in trim hair and a clean shirt; that's good. Then I notice the tufts on his neck and upper lip where he hasn't shaved; the odd socks. He has new teeth - a perfect pair of pearly gnashers which sit incongruously in his wizened bristly jaw, making him look different, cheeky, as if about to break into a grin.

'Marina?' He studies me with a look of intense concentration. He doesn't quite recognise me any more, though I'm not sure whether it's his memory or his eyesight that's failing.

'Marina?' He studies me with a look of intense concentration. He doesn't quite recognise me any more, though I'm not sure whether it's his memory or his eyesight that's failing.

'Pappa. You're looking good. Are you growing a moustache?'

He nods, running his finger over his lip. 'What colour is it?'

'Grey. Grey and white.'

'Ah! Good it's not black.' He winks conspiratorially. 'For political reasons.'

The TV booms from the day room, where half a dozen old ladies are snoozing in armchairs. 'Shall we go into your room? Why are you sitting in the corridor?'

'No no no! I must stay here! I have been ordered to wait here. For ear syringing.'

Feeling indignant on his behalf, I enquire at the nurses' office. The nurse - it's Winston, from Zambia - looks baffled. 'We said we would make an appointment with his GP. But that isn't until Monday.'

Reluctantly, my father lets me wheel him back into his room. It is a large room, with a lovely window overlooking the gardens and a vast view of the sky. This troubles my father. A room like this is a privilege; a room like this, he whispers, has made him enemies.

'Nonsense, Pappa. What enemies?'

'Some persons.' He waves his hands vaguely. 'There is a rumour that they have asked for me to be deported.'

The trouble is, I'm never quite sure. It is possible that he has made enemies, or been bullied. It is possible that someone said he should go back to where he comes from. These things do happen - though it's hard to imagine any of the old ladies dozing in their armchairs could summon up enough energy for bullying. The staff? Lovely cuddly Winston? Sweet efficient Juliet? Kindly bustling Marie? How can I tell?

'I have heard on the radio that there are too many pensioners. Some must be deported.'

'Who said this?'

He shrugs. 'But if I am to be deported, it must be to Odessa.'

He is smiling impishly. Or maybe it's just the new teeth.

'Don't worry. I'm sure it's a misunderstanding.'

'Hmm. So what must I do to be deported?'

'No one is going to deport you, Pappa.'

'I will shout. I will make scandal.' He is beginning to sound quite frisky. 'When police are coming they will arrest me.'

'I don't think they will, Pappa.'

'Have you been in Odessa? Ah! City of marvels! Did I tell you about my uncle who came from there?'

I have heard about this uncle before. He was an optician who lived in Odessa at the turn of the century, and rode around in a coach with four black horses to visit his wealthy clients. Or maybe my father has made it all up, like he made up the ear syringing and the mass deportation of pensioners. We gaze at the clouds and talk about Odessa while the radio plays Brahms in the background and tea cups clink in the day room.

When it is time to leave, he suddenly grips my hand, pulls me towards him. 'Please, Marina! You must help me!' Immediately I feel a flutter of panic. What has happened? Has one of his long-running feuds in the nursing home turned serious?

'I'll try. What's the problem?'

'I am trying to remember a Baudelaire poem. About albatross. Cannot walk on ground.'

Ah. It could be worse. 'I know the one. I studied it for A-level French. I'll bring it next time.'

As I go, he asks me to wheel him back into the corridor.

'Pappa, the ear syringing isn't until Monday.'

But he insists. And I realise it isn't about the syringing at all. It's where he likes to be: waiting on the threshold, neither in nor out.

Later, when I read the Baudelaire poem, I understand something about him, and my heart aches for him - the poet, the stumbling bird, the prince of the clouds, my dad.

The poet is like this prince of the clouds

Who rides on the storm, mocking the archer

But exiled on earth, jeered at and scorned

His giant wings impede him from walking.

![]()

<< Articles page one | << Articles page two | Articles page three